100 Pitches.

Thats a lot of pitches right?

What about 50? Doesn’t seem so bad.

What if the guy who threw 50 pitches also threw 50 pitches in the pen before the game?

Is that not 100 pitches also?

Pitch counts are a big problem in our game today. Coaches hide behind the rules of pitch counts taking the practice of pitch count recommendations as the holy grail of injury prevention.

It’s time we begin to look at a new model. The research collectively does not support the idea of using pitch counts to protect arms. Don’t take my word for it though, here is some excerpts from some of the research…

-“A majority of healthy (actively competing) youth baseball players (76%) report at least some baseline arm pain and fatigue, and many players suffer adverse psychosocial effects from this pain.” (Makhni et al.)

-”Epidemiological studies and personal experience indicate that the incidence of throwing-related injuries in adolescents is on the rise for many reasons.” (Parks et al.)%20is%20highly%20recommended.)

-”The increase in participation in youth baseball and softball with an emphasis on early sport specialization in youth sports activities suggests that there will continue to be a rise in injury rates to young throwers.” (Feeley et al.)

Pitch counts though well intentioned, with the goal to stop fatigue and injury, are a massive problem in our game today as they do not offer useful insights to track fatigue. Let me explain…

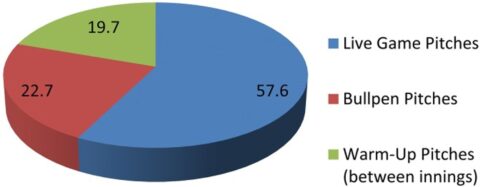

When looking at the number of pitches in a game day I like to reference this study “Unaccounted Workload Factor: Game-Day Pitch Counts in High School Baseball Pitchers—An Observational Study”. In this study they observed 13,769 pitches from Florida based high school athletes and concluded that only nearly half (57%) of the pitches on a game day are what we call pitch counts. The other half of these pitches were from bullpen and warm up pitches between innings. This means using only pitches on a game day, we are making decisions on an athletes readiness to pitch in the future from only half of the pitching specific activity they did that day.

It’s important to note that in this study they did not account for warm up throws, plyocare throws, or even an athlete playing another position. This study also doesn’t account for the throwing that happens on non game days. We cannot overlook the importance of all of these throws and their potential impacts on fatigue. When we begin to account for all of these throws we can begin to see that pitch counts amass for substantially less than 50% of our total throwing but dictate whether or not an athlete should be pitching all the way down to our lowest levels of the game.

This is problematic as other research has identified amateur injury as an indicator for additional future injury.

+”55% of pitchers with a UCL injury had a history of elbow injuries as an adolescent/child.” –(Vance et al.)

+” Pitchers have a high prevalence of UCL reconstruction in professional baseball, with 25% of major league pitchers and 15% of minor league pitchers having a history of the surgery.” – (Conte et al.)

This research indicates the injuries you see from your favorite player in the MLB today could have been in part due to overuse when they were young. No matter the age the injury occurs we know that majority of the time it is a workload issue where an athlete is either underprepared for the load or is over trained.

“Fatigue and inadequate rest were of greatest concern among all pitchers for an increased risk of UCL injuries.” (Vance et al.)

Pitch Counts ARE a form of workload management with the intentions to stop fatigue and injury. The efforts of groups like Pitch Smart (the industry leader in pitch count recommendations) have lead to broad adoption of pitch counts with the intentions to curb fatigue. Again the intentions of pitch counts are good but they simply have not worked due to the limitations around the work that is tracked. Some don’t understand this, but workload management is a broad topic referencing any form of managing the amount of work or load a player sustains.

Let’s be clear here that Pitch Smart is an organization making workload recommendations. Again Ill say it, pitch counts are a form of workload management. Going back to our intro section, it is funny to me to hear people tell me why “workload is too complicated”. Reality is that most who make this claim also use a workload process of some sort daily many adhere to the guidelines of Pitch Smart. The evidence though as referenced is heavily stacked against the workload models that govern innings limits or pitch counts. It is overwhelming the research supporting the fact that we need a better model.

You shouldn’t think that this is an exclusive problem to amateur baseball though. Pro organizations have been equally as guilty of throwing together arbitrary restrictions around players throwing year over year. Some organizations have innings limits they place on their elite arms while some have general pitch count restrictions they increase universally from spring training into season.

We have already established the issues around unaccounted workload and these professional organizations are well aware of the risks. They are confronted with the same issue annually but the lack of response leaves some of the top players in the game to continue to sustain career altering injury.

What is the issue they confront annually? The month of April.

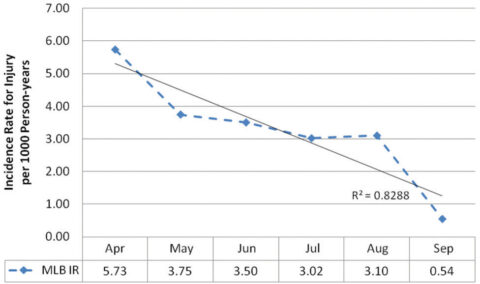

Epidemiology of Major League Baseball injuries

A study called the epidemiology of Major League Baseball points to some hard truths about injury at the highest level. Many would think as the season wears on that athletes would fall injured due to the rigors of the 162 game season. Reality though is year over year MLB teams are confronted with the highest incident rate of injury being April.

What does this tell us about most injuries? It tells us that a large number of MLB players do not build up properly in the offseason, they show up to season undertrained and then become fatigued/ injured in the first few weeks of season.

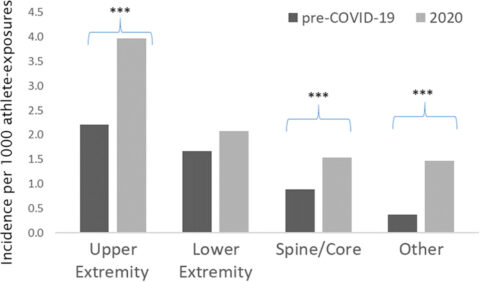

Not sold that improper progression of throwing in the off-season is causing injury? In 2020 we saw just how dangerous the improper progression of throwing can be.

Injury Rates in Major League Baseball During the 2020 COVID-19 Season

I remember presenting to an MLB team the concepts around how we scale workload management to the masses when a member of the staff came into the room and said “hey spring training is closing down. There is a deadly virus that is shutting down everything.” COVID became a national news story and I quickly left Arizona to travel home to Florida.

On my way I was talking to some of our MLB players and it dawned on me, we are about to see a limited window to build up and when these players return to the field we are going to see a massive injury spike. Gyms were closed, players weren’t thinking about throwing, safety and the health of their family was the focus.

In the moment of first realizing the possible problems the MLB faced, I wrote up an article and immediately began to talk to some of the best journalists in the country. Here is an excerpt from an article by Eno Sarris in the Athletic titled “**Sarris: How to avoid a possible injury spike among major league pitchers”.**

““With no games, the question is can pitchers get the needed workload to build up before the season starts,” said Casey Mulholland, founder of KineticPro Performance in Tampa, a facility that trains many major leaguers in normal times. “The repercussions of this time off could greatly alter any future season, but if not managed properly, could alter the careers of many of the game’s top athletes.”

Mulholland predicted that we will see a spike in Tommy John surgeries this year, particularly if the downtime — and the return to action — isn’t managed with a sense of care and a knowledge of the existing research. If this sounds like saber-rattling from outside the league, most of my sources within baseball agreed with him.”

I reposted this article on social media outlets, I did interviews on podcasts trying to tell everyone about the dangers we were facing, I even sent emails to organization front offices trying to get some sort of acknowledgement that their might be a considered solution.

The 2020 season came and went, a short season full of odd moments and forgettable games. With so much going on in the world the idea of tracking injury rates in the MLB wasn’t the first thing on the minds of most. Heck some would’ve told you to be thankful there was a season that happened in the first place. The 2020 season came and went with the commissioner standing out front expelling how great of a job the league did as a whole ,“I think baseball should be proud of what it accomplished this year’’ said Rob Manfred.

Reality is there was a lot to be learned from the 2020 season and when the study “Injury Rates in Major League Baseball During the 2020 COVID-19 Season” was posted it was revealed just how bad the year was for the health of MLB players. A true master class in what not to do from a workload standpoint and a true learning experience for all at the dangers presented by poor workload management.

Reflecting back the question has to be asked, what would it have taken to assure a healthier season? Just a better progression with more time before the season would have started. Simple.

It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to realize that proper progression is key to sustain a healthy season but you might be asking the question what is a “proper progression” when it comes to throwing?

Organizations have offices full of analysts who’s job is to break down everything from how pitches move to how many pitches are being thrown in the year. Using the data they have they devise curious ways to evaluate workload seasonally using advanced algorithms that break down pitch counts or innings limits into what they hope are better prediction systems.

The problem goes back to our main point you cannot track throwing workload when only viewing less than 50% of all throws. These analysts break down pitch counts or innings limits because they typically do not have access to all throws a player makes. In the past this has been in part due to a lack of technology, a lack of understanding of technology or just a general lack of compliance from the player. This doesn’t change the point though. Pitch counts and innings limits are rendered useless without the context surrounding the other throws an athlete completes daily. Though well intentioned you cannon’t establish proper progression without a complete dataset or based on pitch counts/ innings limits alone.

Proper progression into a season is something that is objective in its approach. Proper progression into a season has a goal in mind around how much throwing an athlete must do to be ready for a season. Proper progression into a season must have a rate of progression to which the progression of throwing must follow.

I like to use a simple example to illustrate this, often times this example shows that tracking all throws with a better workload model only makes sense intuitively.

Are you ready to run a marathon today? Most would answer with a resounding “no”.

Why aren’t you ready to run a marathon today? Most would answer “because I haven’t built up”.

Isn’t it funny how we instinctually know this to be true. Most upon being asked this question would identify the fact that a full marathon is roughly 26 miles and that they haven’t trained to handle that much running.

I then continue on with the questioning, “if I give you 6 months to train for a marathon do you think you would be ready run it?” Most slowly begin to consider the task and nod their head yes.

What most begin to consider is the progression rate and try to do some quick math to figure out if 6 months is enough time for them to build up.

I press into the thought process and ask “so week one of training you are going to run 1 mile 3 days a week?”

Long pause with a “sure I think that could be good”.

Then I follow up “week 2 of training Im thinking we do 10 miles 3 times a week”.

Long pause “no no thats way too much for week 2!”

Its instinctual and intuitive. You consider the length of time needed to be ready for the demands you face and you progress slowly in training the skill to be ready for those demands you face. This is proper progression and the idea of it isn’t just for building up in the off-season. Progression and regression matters in season as well.

When looking at the paper “Epidemiology of Major League Baseball injuries “ we already have talked about the dangers of the month of April but its important to note that the only other time injury goes up again in this article is shortly after the All Star break. This is because players who don’t make the All Star team can often be found regressing their throwing workload substantially as they take a mid season trip home or on vacation. Rarely do you find these athletes maintaining their throwing volume through the week. When they return, the load leaves them fatigued and we know when an athlete is fatigued they are at a much higher risk of injury (more on this in our next section).

Pitch counts and innings limits though well intentioned are leaving our game in a difficult position. Looking at athletic performance and health through the subjective lenses of pitch counts and innings limits has left todays game in a dangerous position.

Industry leaders didn’t intend for pitch counts or innings limits to be used this way. Dr. Fleisig of ASMI is quoted in an article saying “pitch counts should be used as “guidelines” rather than “rules,” and that the emphasis should be on spotting and managing fatigue rather than on counting pitches and innings.

“The rule should be that when a pitcher has arm fatigue, he should come out. So when he has arm fatigue, he should not pitch again until the fatigue is gone””. Dr. Fleisig is on the Advisory Committee for Pitch Smart.

As Dr. Fleisig points out and as we have established through this section our real goal is identifying fatigue. Its clear pitch counts and innings limits lack the overall insight to protect our athletes from fatigue but what is the alternative?

In a future blog post we will dive into the discussion of a better solution and we will discuss fatigue as a concept to more fully grasp the injury problem at hand.

To conclude this post though. Let’s all agree. Pitch Counts and Innings Limits are not working. The future of the game, a healthier next generation, depends on us implementing a better model.

Want to get started training with KP? We offer both remote and in person training (Tampa FL).

To get started with remote training: Click Here

To get started with in person training: Click Here